How This Serbian Fresco Became The First Image Sent To Space

Serbia takes its monasteries pretty seriously, and those tranquil complexes are often home to some of the most astounding spiritual art on the continent. One particular fresco has more than just religious history behind it, as it was used in attempts to bridge the gap between ideologies, nations and even universes. This is the story of Serbia’s White Angel.

Anonymous beginnings

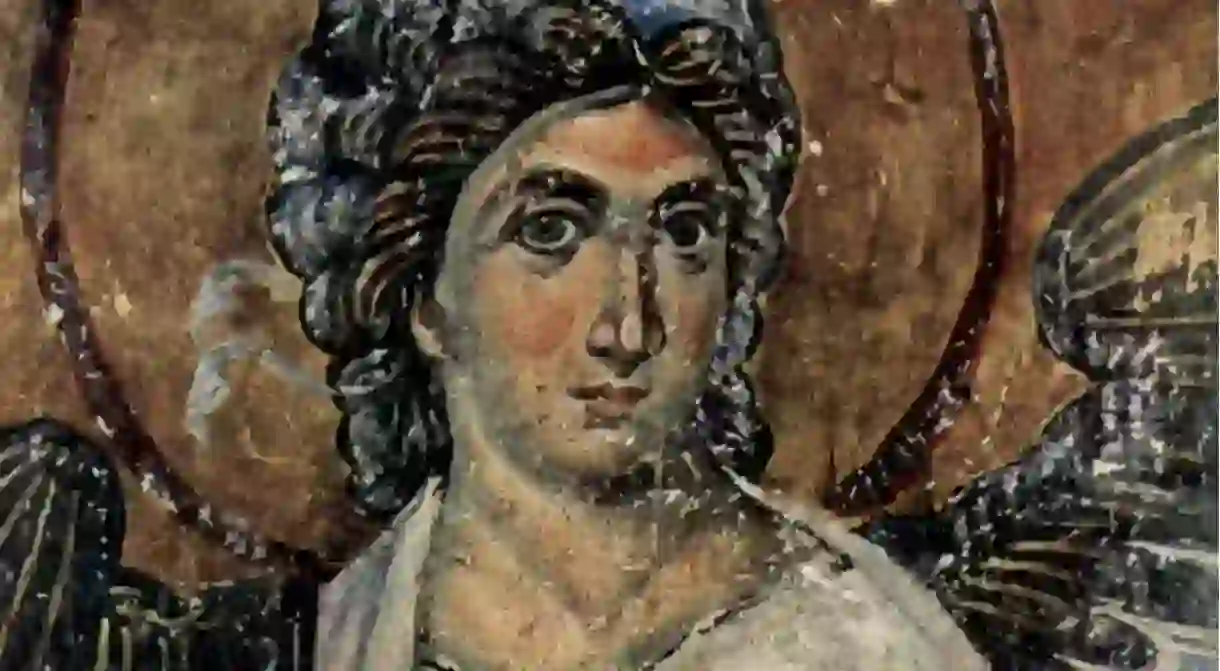

Well, that should really be Serbia’s Beli Anđeo. The fresco in question started life as little more than a choice detail on another piece of art, the early 13th-century Mironosnice na Hristovom grobu (Myrrh-bearers on Christ’s Grave) in the Mileševa Monastery. The androgynous spirit came to symbolise peace and reconciliation between nations, and there was much need for both of those things in the mid- to late-20th century.

With the Cuban Missile Crisis in the rearview mirror, the nations of Europe decided to send a satellite signal to North America in order to extend the hand of peace. The image was sent in 1963, and the picture in question was none other than Serbia’s White Angel. The angel’s forays into space didn’t end there, as the calming beauty was subsequently sent further into space in an attempt to communicate with extra terrestrials. The aliens didn’t respond, although claims that this was because they were shamed by the artistic ability are yet to be confirmed nor denied.

The unknown artist

You’d think the artist behind the first image in space would have men and women queuing up to sing his or her praises, but you’d be wrong. The author of the White Angel is still completely unknown, with many assuming that it was the work of an anonymous Greek artist. The fresco went completely undiscovered for centuries, sitting in Mileševa Monastery along with many other pieces of spiritual art that were revered by all and sundry.

The Ottomans weren’t particularly fond of the Serbs retaining an icon of their own to keep the flame of hope burning, so the decision was made to lay waste to the monasteries and churches of the Serbian Orthodox faith. Mileševa didn’t escape this, and the pinnacle of Turkish repression started here in 1594.

The Serbs had risen up (unsuccessfully) against the Ottomans, and the Grand Vizier made the decision to remove Saint Sava’s remains from Mileševa, take them to Belgrade, and set them on fire on Vračar Hill. The monolithic church that now carries Sava’s name was built on the very same spot.

The resurrection

When Mileševa was restored soon after, the White Angel was actually painted over. The fresco could well have been lost forever, but centuries of degradation saw it begin to peek back through the paint, and it was thus restored in the 20th century. The technique and precision of the painting could finally be properly appreciated, and the White Angel became one of the most important frescoes in all of Serbia.

It retains this position today. It would be an integral part of Serbian spirituality whether or not it had been sent to diffuse tensions in North America or transmitted into space in an attempt to woo the little green men. Bishop Nikolaj Velimirović (who posthumously was granted sainthood) described looking at it as ‘identical to a prayer’. That seems somewhat blasphemous, but who are we to argue with the New Chrysostom?

There are plenty of incredible frescoes in Serbia. The mosaic at Oplenac may be the most artistically impressive, but none carry quite as much weight and historical responsibility as the one that was almost lost by negligence and obliteration. The White Angel is now an international symbol of peace. Maybe the aliens will come round to us soon…